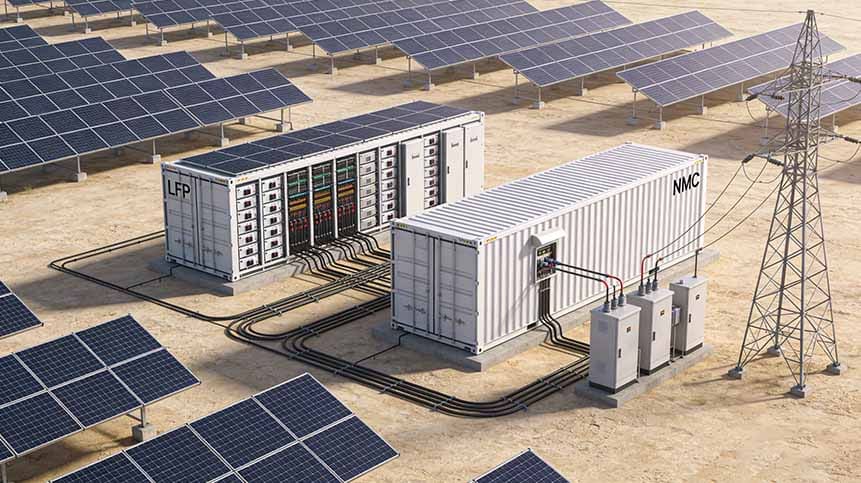

LFP vs NMC for Energy Storage: A Professional and Practical Comparison

Introduction

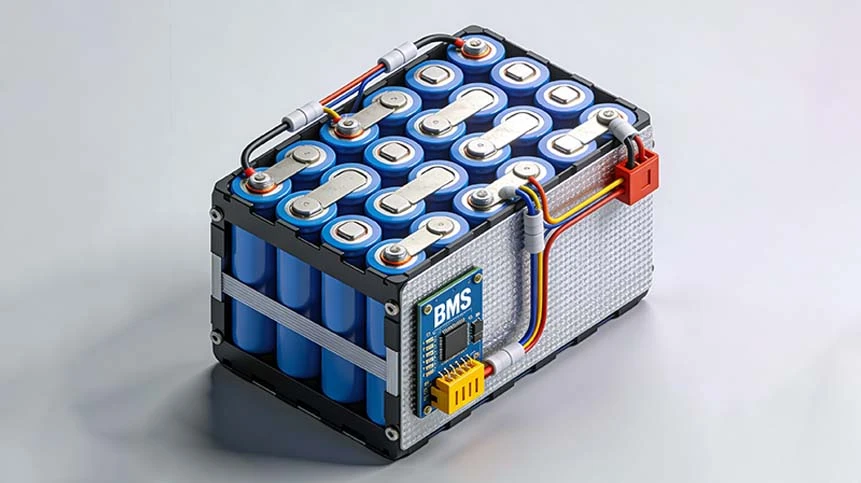

In the world of sustainable energy infrastructure, selecting the right battery chemistry for energy storage systems (ESS) is one of the most consequential decisions a buyer, installer, or engineer will make. Two dominant battery types are Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) and Nickel Manganese Cobalt (NMC) lithium-ion chemistries. While both are lithium-ion based, they differ fundamentally in performance, cost, lifecycle, safety, and long-term value — especially when applied to grid storage, solar + battery systems, and commercial ESS.

In this article, I share my industry experience and research to help you understand what these chemistries are, how they truly compare, and which is the optimal choice for your application, whether residential solar storage, commercial ESS, or utility-scale systems.

What Are LFP and NMC Batteries?

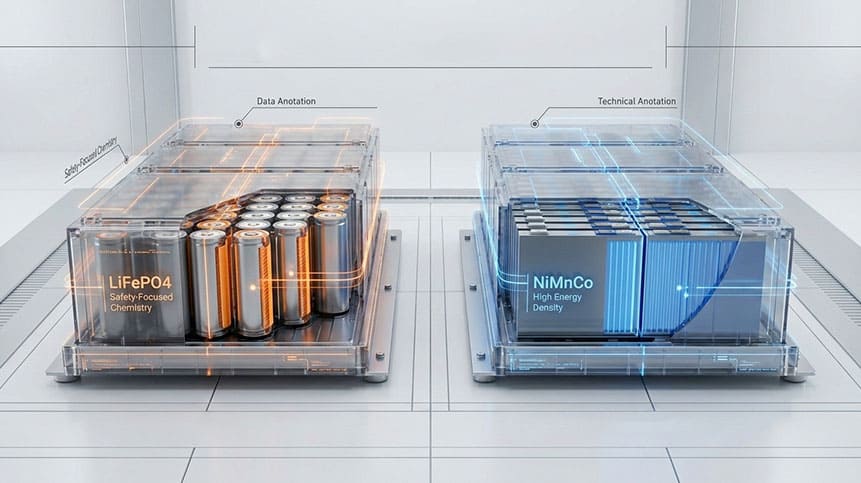

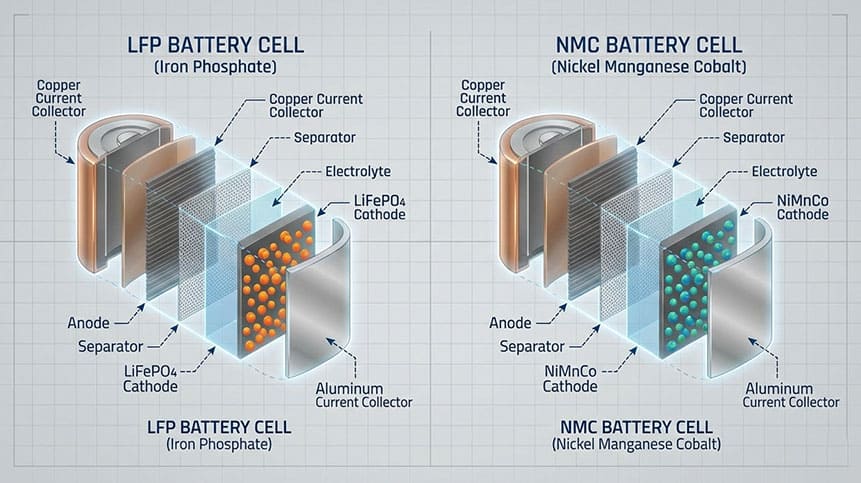

Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP)

LFP batteries use lithium iron phosphate as the cathode material. This chemistry is widely recognized for strong thermal stability, excellent safety, and long cycle life. These characteristics make LFP a popular choice for stationary energy storage, electric buses, and in settings where safety and durability are critical.

Nickel Manganese Cobalt (NMC)

NMC batteries use a blend of nickel, manganese, and cobalt at the cathode. This combination is designed to maximize energy density and power output, enabling smaller and lighter battery packs for a given energy capacity. This is why NMC dominates in high-performance applications like premium EVs and compact portable systems.

Core Comparison Metrics

Energy Density

Energy density determines how much energy a battery can store per unit of mass or volume.

-

NMC batteries typically have higher energy density than LFP, enabling more energy storage per kilogram or smaller footprint, which is crucial when space is limited.

-

LFP batteries have somewhat lower energy density, meaning they may require more space for equivalent stored energy, but that trade-off buys other advantages (see below).

| Metric | LFP | NMC |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Density (Wh/kg) | ~100–170 | ~150–300 |

| Pack Compactness | Lower | Higher |

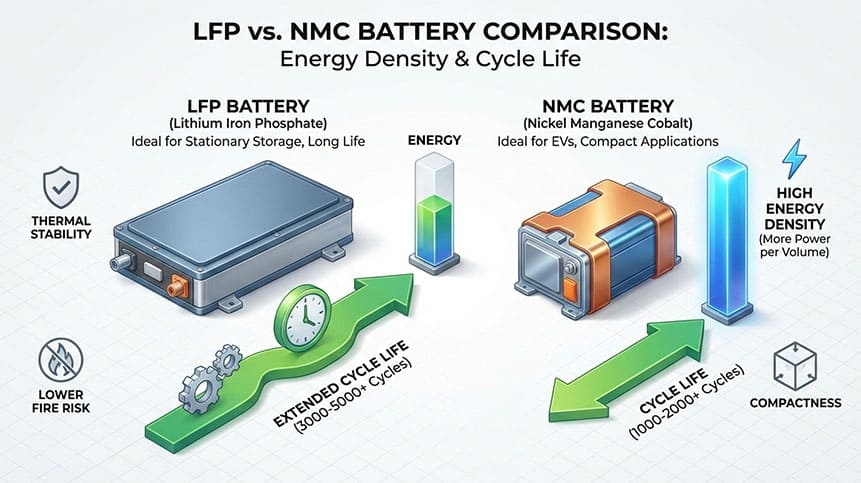

Cycle Life and Lifespan

One of LFP’s standout strengths is its cycle life — the number of complete charge/discharge cycles it can sustain before significant capacity fade.

-

LFP batteries often exceed 3,000–5,000+ cycles under typical conditions.

-

NMC generally achieves 1,000–2,000 cycles before noticeable degradation.

This extended cycle life translates into lower long-term operating costs, especially in ESS where daily cycling is expected.

Safety and Thermal Stability

In energy storage, safety is paramount. A battery that runs cooler and resists thermal runaway lowers risk in residential, commercial, and utility systems.

-

LFP chemistry is more inherently stable, is less prone to overheating, and is seen as less likely to enter thermal runaway than NMC.

-

NMC batteries—due to their nickel content—can have higher thermal risk, requiring stricter management control systems.

This difference makes LFP especially attractive in environments where fire risk mitigation is a priority.

Cost Considerations

Battery cost impacts both upfront CAPEX and total cost of ownership (TCO):

-

LFP materials (iron, phosphate) are abundant and less volatile in price compared to nickel and cobalt.

-

NMC material costs, especially cobalt and nickel, tend to be higher and more supply-constrained, impacting battery cost.

Even though NMC can sometimes be cheaper per kWh in manufacture, the TCO advantage often swings back to LFP due to longer lifespan and lower safety/maintenance costs.

Performance in Real-World Energy Storage

Efficiency and Depth of Discharge

Both LFP and NMC perform well across typical ESS charge/discharge cycles, but:

-

LFP maintains high usable capacity over long periods without rapid degradation.

-

NMC offers faster response and higher power density, useful for grid balancing and frequency regulation.

Thermal Behavior & Geographic Suitability

For installations in hot climates, LFP’s thermal stability is a major benefit. However, NMC can perform better in low-temperature environments with appropriate thermal management.

Environmental, Regulatory & ESG Considerations

Material Sourcing and Environmental Impact

The metals used in NMC, notably cobalt, are not only expensive but have supply chain and ethical concerns due to concentrated mining regions.

In contrast, LFP’s reliance on iron and phosphate ties to abundant, lower-risk minerals — a factor many ESG-focused organizations weigh heavily.

Regulatory Trends

Emerging battery regulations in the EU and U.S. increasingly emphasize carbon intensity and critical mineral sourcing, often benefiting LFP chemistries due to lower embodied carbon and less risk of supply chain disruption.

When to Choose LFP vs NMC

Choose LFP When

✔ Long lifespan and cycle life counts

✔ Safety is mission critical

✔ Lower long-term operating cost matters

✔ Applications include residential solar storage, commercial ESS, backup power

Choose NMC When

✔ Energy density or compact footprint is critical

✔ Fast response and high power density are priorities

✔ Added cost is acceptable for specific performance gains

In many real deployments, the choice boils down to application priorities more than any single battery metric.

Data Tables (Side-by-Side Comparison)

| Feature | LFP | NMC |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Density | Lower | Higher |

| Cycle Life | Higher | Moderate |

| Thermal Safety | Excellent | Good, requires management |

| Cost | Lower TCO | Often higher material cost |

| ESG / Supply Risk | Lower | Higher |

References

FAQ

Q1: Is LFP better than NMC for home energy storage?

A: For most home & commercial energy storage applications, LFP is preferred due to safety, lifespan, and lower long-term cost.

Q2: Does NMC offer higher energy density than LFP?

A: Yes, NMC batteries typically store more energy per kg than LFP, which is advantageous in systems with space constraints.

Q3: Are LFP batteries safer?

A: Yes. The chemical stability of LFP reduces the risk of thermal runaway compared to NMC.

Conclusion

Choosing between LFP and NMC for energy storage is not a one-size-fits-all decision. It depends on your performance requirements, safety priorities, cost budget, and long-term operational goals. In many stationary energy storage deployments today, LFP emerges as the balanced choice, delivering long life, lower operational cost, robust safety, and strong ESG positioning. NMC still plays a vital role when energy density and space limitations are the deciding factors.

If you want to design a future-proof, safe, and cost-effective ESS, LFP often provides the most sustainable value over time — particularly in renewable and utility contexts.

-

May.2026.03.03Sodium Batteries and Lithium-Ion Batteries: Low-End Substitutes or Strategic Complements?Learn More

May.2026.03.03Sodium Batteries and Lithium-Ion Batteries: Low-End Substitutes or Strategic Complements?Learn More -

May.2026.02.27Lithium-Ion Batteries: The Six Constraints Blocking the Path to PerfectionLearn More

May.2026.02.27Lithium-Ion Batteries: The Six Constraints Blocking the Path to PerfectionLearn More -

May.2026.02.25Li-Polymer Battery 5000mAh: Complete Technical & OEM GuideLearn More

May.2026.02.25Li-Polymer Battery 5000mAh: Complete Technical & OEM GuideLearn More -

May.2026.02.24The Unparalleled Advantages of Lithium-Ion Batteries Over Traditional BatteriesLearn More

May.2026.02.24The Unparalleled Advantages of Lithium-Ion Batteries Over Traditional BatteriesLearn More -

May.2026.02.243.6 Volt Battery: Complete Technical Guide for Engineers & BuyersLearn More

May.2026.02.243.6 Volt Battery: Complete Technical Guide for Engineers & BuyersLearn More